Written by Masafumi Matsumoto, a BJJ black belt from Japan who has been traveling the world, training, competing and working as a translator. ‘Masa’ is known for having a very good guard, especially his spider guard.

Have you ever felt hopeless about passing your training partner’s guard, and felt that you don’t really know what to do about it?

If you have, what you will read in the following might help you understand what’s going on when you try to pass someone’s guard.

But why should you listen to me on this matter?

No, I’m not a world champion or anything like that, but I consider myself as a competitive brown belt, and play the guard a lot. Also, I’ve been traveling around the world in the last few years, and had some opportunities to roll with a bunch of different people from different parts of the world.

I noticed that there are common mistakes people make when they try to pass my guard, and I hope to share with you some observations about what these mistakes are, and what could be done to avoid them.

Now… common mistakes.

The first one is the most common, and probably the most important.

1. You’re not in a dominant position to start passing the guard.

Trying to pass your opponent’s guard when you’re not in a dominant position to do so is suicidal.

Imagine your opponent is controlling you with spider guard. What you should do is not the knee slide pass despite the spider control, but to get rid of your opponent’s foot on your bicep and to break any dominant grip your opponent has on you.

I know this may sound too obvious and you may know this intellectually, but if you have some difficulties passing your training partner’s guard and you somehow get triangle choked or swept during your guard passing attempt–slow down and observer what’s happening to you, because there’s no “somehow”.

Keep in mind–you have to find a dominant position before initiating a pass. And finding a dominant position often means you have dominant grips and a solid structure that gives you a huge advantage in controlling your opponent’s range of motions just by placing your hands and legs in a certain position (i.e. creating frames to block your opponent’s movements).

Just because you’re on your feet and your opponent is taking the guard position, it doesn’t mean you have to work on guard passing straight away. Instead, try to get to a dominant position, from which you can safely start passing your opponent’s guard.

Sounds good?

OK, let’s move on to the next problem.

2. You’re not pressuring your opponent at all.

Some people try to do a speed race and try to run past their opponent’s guard (figuratively, though some might do that actually). Or others prefer to do some acrobatic moves by jumping around. But if there’s no pressure, your opponent can move around, and possibly follow you with no problem, especially if he/she has good guard skills.

Or perhaps… you might even have some grips on your opponent’s pants, but if you don’t use these grips and your whole body to pressure your opponent, then you need to start giving pressure to your opponent. You can’t just hope that something good will happen (and/or nothing bad will happen) to you.

There’s something more I want to say about pressure.

It’s not about throwing your opponent’s legs with your brute strength at once — pressure needs to be constant while you work on your pass.

This leads to the third problem I want to talk about.

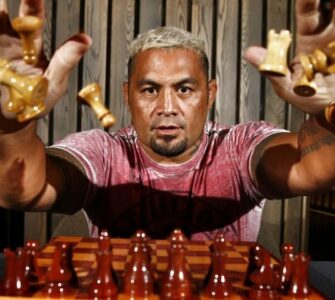

Masafumi Matsumoto (author)

Photo: Jits.com

3. Your pressure is sporadic and not constant.

This is crucial.

If you try to pass someone who has good guard skills, you don’t want to create any space when you move from A to B.

And to give constant pressure, you can’t just rely on strength or speed, but you have to use your whole body.

You must get dominant grips and take a structurally safe position–what I mean by a “structurally safe” position is where you can control your opponent’s movements by placing your legs and arms in such a way that you can use your bodyweight to control smaller and weaker areas of your opponent’s body.

My understanding is that “giving pressure” means achieving two of the following: (1) restricting your opponent’s range of motions with your arms and legs and everything else, and (2) distributing your bodyweight in such a way that it adds further control to (1). There may be other criteria, but I believe these two are essential in giving pressure to your opponent’s guard.

For example, if you want to restrict your opponent’s hip movements, I believe there are two broad types of moves you can do: you either spread your opponent’s legs to the extent he/she cannot close his/her legs at will, or fold his/her legs to the extent he/she cannot open his/her legs at will. (e.g. Knee slide and over/under are of the spread type; leg drag and stack pass are of the fold type. Either way, you have to use your whole body to spread or fold your opponent’s legs.)

***

So, in a nutshell, when you roll next time, make sure to take a safe and dominant position before initiating a pass, and work on blocking your opponent’s movements rather than trying to jump over his/her guard at once.

These may sound obvious, but it takes a lot of practice for your body to understand these concepts and to be able to perform them on an intuitive level.

Remember–the “survival first” rule applies here as well.

As long as you don’t get submitted or swept, you’re still good to go.