What do you define as a fundamental grappling technique? For most BJJ practitioners this usually includes the arm bar, the kimura, and the triangle, usually all from guard and followed by side control. We learn these from the outset, sometimes throwing up fifty or so in a warm up. We consider these to be fundamentals, but I’m not sure this should be the case.

I would argue that you can in fact practice BJJ without using submissions at all – you would of course be cutting out a huge part of the game, and what makes it attractive and effective for most people, but nonetheless it would still be BJJ and would still be useful. You could still win competitions on points, and from a self-defense point of view you can escape an attacker and gain top position, or at least stand up. And if you look more broadly, to other arts, the ‘fundamental’ techniques become entirely different.

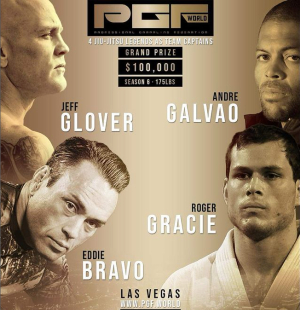

Compare two very different schools of grappling: freestyle wrestlers and 10th planet students. The techniques that each of these groups learn could not be more different, yet both of these are grappling arts, part of the same continuum. I expect a skilled practitioner in one has all the fundamental understanding to become skilled in the other, even if they need to develop a whole new arsenal. In fact, you do not even need to look outside of BJJ to see wildly different basic techniques: if you were to see an IBJJF gi comp and a no-gi sub only comp it could be hard to reconcile them as the same sport. You might look at sport sambo and think that it fell right between these two, and yet sambo is considered something entirely different. In both sambo and catch wrestling, leg locks are taught early on, but most BJJ school consider them advanced and dangerous – I’m sure you’ve seen someone refer to them as the ‘dark arts’ for this reason. I suppose this is why I don’t really consider myself a BJJ practitioner, but instead more of a ‘grappler’. BJJ is so broad that it could be considered any sort of grappling with a focus on ground game, and even when you consider arts with more of an emphasis on the standing elements there is a wealth of knowledge that can be transferred. So what are the fundamentals of grappling?

The fundamentals of grappling, I argue, are not techniques, but concepts and principles. Beginners usually reach a point a couple of months in where their ability rockets: they start to hit submissions, manage sweeps, and everything begins to click that much faster. They gain an intuitive understanding of those most basic principles: control, balance, and leverage. I think this is true of any grappling art, whether it is judo, folkstyle, or anything else. Techniques themselves are not truly what any grappling art is built on. I am not saying that there are no complex techniques; a twister is clearly more complicated than a guillotine, but then so is a triangle, and it is usually the triangle that is taught first. And I do understand that the consequences of a heel hook are much worse than of an arm bar – the sub comes on fast, and tendon damage to your knees could affect you for life – but it’s actually extremely hard to cripple someone with a kneebar, and I’ve never felt damage from having my knee ‘reaped’. Not to mention that rotatory cuff damage, from say a kimura (commonly considered a basic move in BJJ) can also have life long consequences. No, I don’t think most leg locks are frowned upon in BJJ because they’re dangerous, I think its just an excuse to shape the art. Overall, it’s not the complexity or the danger of a move that makes it ‘fundamental’, and it all seems pretty arbitrary to me. Quite honestly I can’t see any good system that we can use to categorize the term ‘fundamental’, nor any reason why we need to.

So what’s the point of all this? Well, if grappling is built on principles and not techniques, then we can use that to influence our training, and re-evaluate how valuable certain things are. For example, I think the best BJJ classes are the ones that develop my understanding of concepts, rather than just showing me a variety of different moves. Few of us remember techniques after being shown and practicing them in just one class – realistically we probably practice those few techniques that we use more while rolling than any other time. It’s not that you shouldn’t drill techniques – you should of course refine your moves as best you can, and work out how to make your submissions as effective as possible, but that’s like learning to shoot if you want to win a battle: it’s just one piece of the puzzle. A move, you might forget, but understanding is something you can build upon each and every time, in tiny increments. This is also why I think many seminars are overpriced, and not likely to improve your game a great deal. On the other hand, seminars that look at the principles of different positions and strategies are incredibly useful, and developing understanding in the mind of students is the mark of a really great coach. I think that’s what sets instructors like Ryan Hall and John Danaher apart from everyone else. Others might have the same, or perhaps even greater technical knowledge (maybe not than Danaher) but these are the coaches that really develop the minds of their students.

In the end, everything comes back to balance, control, and leverage. Posture when on top? It’s about control through pressure and wedges, keeping a good base to maintain your balance, and getting ready to apply proper leverage when you move to the submission. Position on the bottom? Limiting your opponents ability to apply leverage, setting up your own opportunities to do the same, preparing to disrupt balance if you want to sweep, and controlling your opponent to prevent them advancing position. Subsystems are the same. Both the open elbow and inside senkaku are about control of position in order to apply proper leverage. Other strategies might enhance one aspect and limit the others. Creating scrambles reduces the control of either grappler, in order to create more chaos and open opportunities, while stalling does the opposite, increasing the control aspect massively while limiting opportunities for both parties, and also reducing the ability of the opponent to apply leverage. Everything you do can be broken down into how it influences balance, control, and leverage, and I think this is the most effective way to develop any strategy.

If principles are the fundamentals of BJJ (and grappling in general) then it stands to reason that developing our understanding of these principles is more important than developing our knowledge of different techniques. It is not more complicated moves that we should progress to as we develop, but more complicated ideas. From the basic principles of control, balance, and leverage, emerges a more sophisticated understanding of what positions are strong and weak that can be transferred to any grappling art. And if this is the measure of our development, we should re-evaluate our learning tools and methods to reflect this. It is through understanding that strategies and systems can emerge, and I think this is the true measure of our progress as grapplers.

P.S. I would like to credit my coach, Dan (@conditioningforcombat on Instagram and Daniel Bourne on YouTube) with essentially giving me the whole concept of this article. That balance and leverage are the real fundamentals was basically his idea, I just ran with it as best I could. He’s also who got me thinking about what makes a great coach – not by explaining to me why, but just by being one.

Written by R. Diserens