Guest post from Thomas Nadelhoffer the Grumpy Grappler, an Associate Professor of Philosophy, Psychology, and Neuroscience at College of Charleston (SC). When he’s not enjoying time with his wife and pups in the lovely lowcountry, he’s obsessed with the grappling arts. He has traveled the country and the world as part of his ongoing jiu jitsu journey and he hopes to do more exploring soon.

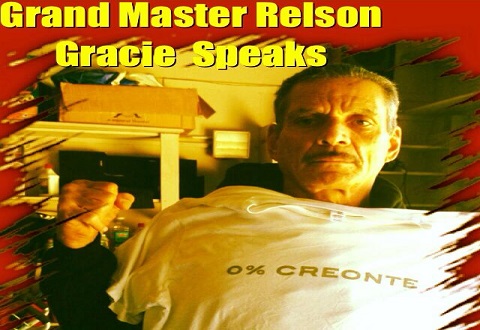

As this image shows, Grandmaster Relson Gracie doesn’t care for creontes–that is, jiu jitsu traitors, the lowest of the low! As someone who received my purple belt from Relson shortly before switching gyms–thereby seemingly violating one of the fundamental rules of traditional jiu jitsu–I thought I would give my two cents on the history of the charge of creonteism! For starters, what does it mean to be a creonte? Originally, “Creonte” was the name of a character in a popular soap opera in Brazil–a character who regularly displayed a lack of loyalty to those who helped him in the past. In short, Creonte was a purely self-interested traitor–someone to be both distrusted and despised.

Later, Grandmaster Carlson Gracie adopted the name as a label for high level jiu jitsu students who switched schools and hence switched allegiances–which was ironic given that one of the key differences that led to the split between Carlson and Grandmaster Helio Gracie was that Carlson was willing to teach the “secret” Gracie techniques and not just the self defense curriculum (see below for more on this issue). Since Carlson began calling his ex-students creontes, it has unsurprisingly always been a term of derision in the jiu jitsu world. To be labeled as a creonte is to be identified as someone who ought to be outright ostracized. As such, being a creonte was traditionally one of the central sins of old school jiu jitsu and a label the Gracies (and their students and followers) took very seriously. On this view, a creonte is someone who steals secret techniques under confidence and then shares them with rivals at other schools. So, not only is a creonte disloyal and distrusted, but he is a thief of techniques as well! But should the label “creonte” still be used and taken seriously today? In short, no.

On the one hand, with the advent of the internet, there are no secret techniques. Indeed, when people come up with new techniques, they often share them with the world without giving it two thoughts (see here and here, for instance). Moreover, back in the days when the term “creonte” took hold, there weren’t books and instructional videos, they didn’t have much competition video to watch, etc. As a result, knowledge was more bottled up and those who had it didn’t like it’s being shared with people who weren’t paying their dues! This secret knowledge was often the key to success for instructors, students, and competitors alike. Consequently, to divulge these secrets was viewed as a major betrayal. But in light of the march of technological progress–and the widespread availability of public knowledge it has fortunately facilitated–the code of sworn jiu jitsu secrecy has become a historical relic. Jiu jitsu is something that should be shared not just with one’s own students, but with anyone interested in sharing the knowledge. So, while it’s obviously fine for people to want to be paid for their expertise–no one’s suggesting the knowledge should be free!–there should be no expectation that the knowledge learned won’t be shared with friends, fellow grapplers at other schools, etc. Jiu jitsu can only continue to grow as an art as its knowledge base expands around the world. This calls for open access to the ever-growing knowledge base of jiu jitsu, not outdated shrouds of secrecy.

On the other hand, there are important cultural differences between the Brazil of yesterday and America today. For instance, as a general rule, Brazilians are far less transient than Americans. So, it’s not uncommon for Brazilians to live in the same city for most (if not all) of their lives–e.g., my wife comes from Porto Alegre (Brazil) where she is still in touch with friends from kindergarten. This makes changing teams less necessary and more noticeable/visible. But Americans move around a lot these days. In my own case, between 2005 and 2014, I lived in Tallahassee, FL, Carlisle, PA, Santa Barbara, CA, Durham, NC, and Charleston, SC. I have trained in each town–sometimes at the same gym, sometimes at different gyms. Does this make me a creonte? Perhaps, but if so, why should I care? Sometimes, people move from one town to another which gives them no choice but to either join a different gym and team–for instance, switching from Gracie Barra to Relson Gracie–or quit training altogether. Sometimes, people move between gyms within the same town because some gyms are better fits given their unique goals, personality, etc. The thought that a grappler who goes from white belt to blue belt with one gym–a gym he selected before he could have known what kind of gym would best fit his preferences, style, and goals–is somehow forevermore obligated to remain loyal to this first gym is simply ridiculous.

While jiu jitsu can be a lifestyle for some, in addition to being both a system of self-defense and a competitive sport–it also often involves a business arrangement. However friendly this arrangement can sometimes be, students nevertheless have the right–as consumers, as competitors, and as students of jiu jitsu–to move around to different gyms, share their knowledge, try to improve upon their game, and widen the base of knowledge of a sport they love.

This kind of behavior ought not be belittled as a betrayal, at best, or a theft, at worst! It is nothing more than a personal journey to master as much of this neverending martial art as possible while one can. Instead, the dreaded creontes we deride ought to be applauded for doing their small part to help the public knowledge base of jiu jitsu grow rather than bottling it up and reserving it for only the loyal few. Even the great Carlson Gracie himself was a creonte, techniquely conceived! If this is right, then shouldn’t we all be creonte and proud? [Yes, this is a lame X-men reference!]

Pedro Sauer blackbelt Keith Owen disagrees in his piece on creontism over at From the Ground Up. While he concedes that white and blue belts have the right to switch gyms, teams, etc., he has a different stance when it comes to advanced belts like me who switch teams. Here is what he says:

What I don’t accept is a medium to high level student who has been training for years, proclaiming to love his school, the people, the instructor and the training who for one reason or another decides to leave to better himself through another instructor’s promises of quick belt promotions, teaching opportunities or promises of free tuition. I refer to this kind of student as “a piece of crap”, in other words a Creonte. It’s happened to me before including taking some of my students with him! What are you to do?

Owens goes on to suggest that before the charge of creonte is made and blame assigned, the instructor must first take a look in the mirror. As he says:

If you are an instructor who has experienced this as I have you need to turn the focus back on you and ask yourself (as I did) some fundamental questions, Am I really giving the VERY best classes I can? Am I up on the latest techniques of Jiu-Jitsu? Do I really want my students better than me? Am I doing my best to make my students succeed? Am I fair in my promotions? Am I NOT playing favorites with some students at the expense of others?

Assuming the instructor has fulfilled his duties and obligations, Owens thinks the blame is to be placed on the shoulders of the traiterous piece of crap students who leave for what they perceive to be greener grappling pastures. But why think this? Is it simply because some students decide to “better themselves” when a good opportunity presents itself–e.g., finding a club that better suits their interests and goals? That seems like an odd target for moral disapprobation! I suspect it’s because Owen seems to assume that higher belts would only leave because of “quick belt promotions, teaching opportunities, or free tuition.” But even if this were true–which it’s not, but more on that in a minute–I still don’t see why that would make someone a so-called piece of crap–especially the latter two. What if a student’s ultimate goal is to teach or open his own gym? What if he loves jiu jitsu but is nevertheless completely broke? Aren’t these legitimate reasons to move to a gym that will better address these goals or needs if one’s present gym can’t?

But setting these issues aside, I think the biggest shortcoming of Owen’s attitude is his uncharitability when judging those who leave. After all, life is complicated and one might have a multitude of reasons for leaving one gym for another that need not entail that one is being a shitty person, a disloyal thief, a jiu jitsu traitor, etc. To think otherwise is to indulge in moral myopia, at best, and moral juvenalia, at worst. At the end of the day, I think that the charge of creonte is bullshit. It is an outdated notion that ought to make it’s way to the dustbin of the history of jiu jitsu. None of this is to say that some people don’t fit the label of “creonte.” But in those cases, it’s more likely because the people are duplicitous assholes that earn our ire. The mere fact that they switched gyms is a red herriing. After all, students can switch gyms while being both open and respectful to the friends and instrutors being left behind. To the extent that’s true, the charge of creonte starts to lose much of its sense. Or so it seems to me.

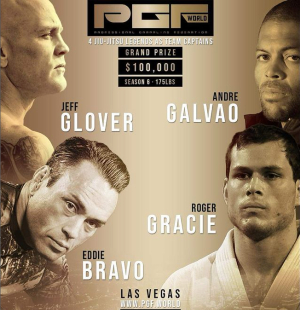

That said, here are some older pieces (here and here) I found about the the dreaded creonte! And here are some funny pictures: