Source: Grapple arts

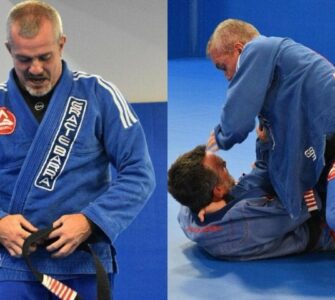

For the people who have never met you or don’t know anything about you, why don’t you take us a little bit through your martial arts history? I know you didn’t start in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. You started with the more traditional martial arts.

Roy: It was definitely a progression. When I was 16, I was sent to Japan as a Rotary exchange student. And while I was over there, they asked me to do a Japanese art after school. I had a couple of different choices. I could do Kyudo, which is archery, Ikebana, which is flower arranging, but I chose Judo. They warned me, “oh, Judo training is very severe,” but I was ready for it. I wanted to work out my energy. So I started training with my high school Judo team, which is similar to an American high school wrestling team. And I trained 6 days a week, competed once a month and really immersed myself in it. By the time I came back to the States, I had won enough competitions to receive my first-degree black belt, and then I just kept on going. Training wasn’t the same in the US. So I started to look elsewhere and ended up in Aikido.

I did Aikido for a number of years, then decided to get serious about it and moved into the dojo of an Aikido and Japanese Jujutsu master, named Julio Toribio. Sensei Toribio was in Monterey, California. So I moved from my hometown of Anchorage, Alaska to Monterey, California, lived in the dojo for 18 months, trained every class everyday and studied Japanese Jujutsu, Iaido, and continued to train.

During that time when I was actually living in the dojo, a friend introduced me to Claudio Franca, who was one of the first Brazilians in Northern California with a legitimate black belt in BJJ. So I began training with him and eventually received my blue belt under him. By the time I moved to Southern California, San Diego, to continue my university education, and I got hooked up with Roy Harris.

During that time when I was actually living in the dojo, a friend introduced me to Claudio Franca, who was one of the first Brazilians in Northern California with a legitimate black belt in BJJ. So I began training with him and eventually received my blue belt under him. By the time I moved to Southern California, San Diego, to continue my university education, and I got hooked up with Roy Harris.

People always talk about how wrestling is a great basis for things like MMA. Even if you end up being more of a striking-oriented MMA guy, then the background of wrestling gives you that mental toughness. So do you think there’s a similar carry-over from Judo into Brazilian Jiu-jitsu, and/or Judo into submission grappling? What’s the relationship between those 2 arts?

That’s an excellent question. There is definitely carry-over between Judo and BJJ. If you start out in Judo, and if you can then empty your cup and be very receptive to the approach of BJJ, you’re going to come out ahead. I mean, just the emphasis on Osaekomi or immobilizations; being able to hold down your partner. Or the speed that is necessary in Judo. Or the sheer number of repetitions that you have to do in order to ingrain a throw in your muscular memory. Sometimes on the ground, guys will be like, “yeah, I did the arm bar like 4 times each side, let’s move on to the next thing.” Judo teaches you early on that when it comes to repetition, you need more like like 400 times each side…

I don’t have that much experience in wrestling. As a brown belt I did attend a wrestling camp, Mark Munoz and Urijah Faber were the coaches there, and it was very, very instructive for me to understand the wrestling mentality and it’s different. A lot of wrestlers want to be as good as they can, as quick as they can, so they may not like the Gi. They only want to do submission wrestling. They just want to maintain top position and they feel that that’s winning. But on the other hand, because of the wrestling, they understand takedowns better, they understand repetitions, they understand being aggressive and how small those windows of opportunity can be if you set someone up for a shot. Plus the ability to generate pressure from up top, which wrestlers are excellent at. So having that background is a huge advantage. That puts them further ahead.

Obviously the rules of the sport dictate the training approach, and even the strategy for a match. Things are really compressed in Judo. Things are even more compressed in wrestling, but they’re both valuable arts and I don’t really see that much difference between BJJ, Judo and wrestling. To me, they’re all grappling arts and, in a way, they’re all arts of angles, distraction and leverage, which I feel is jiu-jitsu.

Well, we’ve talked about Judo, we’ve talked about wrestling. You mentioned another martial art that’s typically not thought of as very combative, and that’s Aikido. Can you talk a bit about what you learned from Aikido which you then use on the mat in jiu-jitsu?

There are so many lessons in Aikido that I’ve been able to translate over to jiu jitsu of all kinds, and BJJ. The thing with Aikido is it is generally considered a cooperative martial art, a non-violent, purely defensive, cooperative martial art. When someone comes in with a strike you have to be able to corkscrew your hips in order to generate power, you drop your hips and corkscrew your hips. And if you’re doing BJJ, you’re doing the same thing but you’re doing it in the opposite direction. When you are on your back and you shoot your hips up and corkscrew for an arm lock, that’s the same motion. It’s just, in Aikido, if you’re doing a wristlock, you corkscrew your hips down. In BJJ, you corkscrew your hips up. So, it helps to understand body mechanics. It gives you the green light to go ahead and blend with your partner. In my own particular BJJ style, there’s a lot of blending. I can sort of enforce my will and generate a lot of pressure, but generally, if somebody’s stronger, I just recognize, “oh man, that guy’s stronger,” and I’ll try to blend with it as much as possible.

So Aikido, like all martial arts, goes in and out of popularity. But it’s powerful. And if you get together with a really good practitioner of Aikido, it can be impressive and it’s not to be underestimated. That’s the first rule of being a martial artist. Respect everyone. Don’t underestimate anybody because that can be a bad day for you.

The wristlock is a great technique to carry-over. You can apply it standing. And it’s even better on the ground because you’ve eliminated all the movement options. Let’s say that somebody almost gets you in a wristlock when you’re standing; you have a chance to get out of it by moving to the third point or wherever they’re trying to throw you. But on the ground, if you pass the guard and have someone in side control, your shin might be over their bicep, and now you use your hand to press down on their wrist, their elbow is backstopped against the ground. They can’t move. They are done.

I think that Aikido could definitely benefit from incorporating a little more resistance in their training method. Their argument says that it can’t be done, but when I first encountered BJJ, I was like “there’s no way guys can do this without getting injured.” But of course it IS possible. Every once in a while, you get a little tweak, but you can do more than you think with resistance and learn quite a bit. I think Aikido could definitely use a little bit of Kano’s innovation of randori.

Obviously, every time you step on the mat and spar with somebody, it’s a form of competition but let’s talk about the big picture, like the official version of competition where you’re going to a tournament. How much of that have you done?

Roy: I’ve done a fair amount. I competed every month in Japan doing Judo competitions. When I was a blue belt, I competed quite a bit. The competition scene was much smaller in those days. It was mainly Northern California, where I was training, so United Gracie tournaments and the US Open, Claudio Franca’s tournament. And then when I moved to Southern California, blue belt, purple belt, I continued to compete.

And competition, for me, was part of the process. I wanted to see what I could do. I wanted to go out there and I wanted to improve and I knew the competition. The best guys were competing. The guys I admired were competing and I want to be like them. I wanted those skills. I want to be able to go out in competition and represent. And I lost every match until I won my first competition, which was Grapplers Quest. It was great. I wouldn’t trade any of those competition experiences for anything.

If my students want to compete, I, first of all, pick a good competition for them to do because not all competitions are the same. And I try to facilitate a good experience for that.

I’m not competing anymore. I don’t feel the fire that I used to. And honestly, if you’re not really fired up about a competition, if you’re not incredibly motivated to go out there and win, then, at high levels, you shouldn’t be out there because guys are hungry. They’re very, very hungry to win, and if the fire isn’t in the belly anymore, there are other challenges in life where you can invest your energy.

But the competition experiences that I did partake in were fantastic and I was happy I was able to win some competitions and just to be able to pass that on to my students, if they choose to go in that direction.