There seems to be some difference of opinion on whether allowing so-called performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) in Brazilian jiu jitsu, mixed martial arts (MMA), and other sports should be tolerated or not. Here are two reasons why they shouldn’t: harm against yourself and harm against others.

Not all sports are alike, but most seem to have some level of PED use. A study of 37 Olympic sports and the percentage of athletes caught using some form of doping in 2010 found offenders in every single sport, from below 1 percent (badminton, skating, luge), to close to 3 percent (weightlifting, boxing, cycling, hockey/ice hockey). Table tennis was at nearly 2 percent (granted, that was only five athletes, but for table tennis?). That doesn’t include professional sports, where the rates may be higher, maybe requiring rehab treatment facilities for drug abuse.

Some fans and professionals don’t see the harm. PED abuse is rampant, but it has made many sports more exciting and increased their audience.

The greatest recent doping scandal among U.S. athletes may be Lance Armstrong, who won seven consecutive Tour de France titles, despite a bout of testicular cancer, with a sophisticated and systematic course of various PEDs. Yes, Armstrong broke the rules, but he wasn’t the only one or the first one; he was just the best at it. That he recovered from cancer and still managed to win so many Tours suggests to some people that rather than punishing him for what he did – with revocation of his trophies or mandating a detox at rehab treatment facilities – we should be asking him to show us exactly how he did it.

Baseball has had several PED scandals of its own – including Roger Clemens, Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, and Jose Canseco among them – complicating Hall of Fame nominations and the record books. But lots of other players similarly abused PEDs without similar success. Many also credit Sosa and McGwire for saving baseball from public disinterest with their home run duel.

Others argue that PEDs are banned for a reason: they are harmful to the bodies of the athletes using them. By turning a blind eye, we are encouraging young athletes to do the same to keep up or to be like their idols.

Ian Shoales (the alter ego of comedian Merle Kessler) of the Duck’s Breath Mystery Theatre comedy troupe once said, “Football players, like prostitutes, are in the business of ruining their bodies for the pleasure of strangers.” I think he was speaking primarily of the physical damage to their bodies caused by playing the sport, such as concussions, but that also could apply to using PEDs because they also harm the body. Many a true word is spoken in jest.

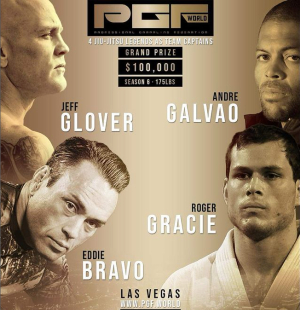

How BJJ Athletes Are Able To Cheat the IBJJF Worlds PED Test

The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) has identified several types of PEDs and their negative effects:

Anabolic agents, such as steroids and testosterone.

Human growth hormone (HGH), erythropoietin (EPO), insulin, and related substances.

Beta-2 agonists and glucocorticosteroids.

Beta blockers.

Diuretics.

Stimulants.

Narcotic painkillers, such as opioids.

Cannabinoids (marijuana and synthetic substances similar to marijuana).

Blood doping with transfusions and/or synthetic oxygen carriers.

While all of the above can create health problems and can be psychologically addictive, both stimulants and narcotics also can lead to physical addictions. Getting clean might require a stay at rehab treatment facilities.

Then there’s the argument that any harm done to the athlete is a matter of personal choice, as many football fans now argue about the dangers of concussions. However there is still the issue of harm against others. Not every athlete is using PEDs, and those that don’t are more vulnerable to injury from the enhanced performance of those that do. Even fellow PED users might suffer crippling or life-threatening injuries.

Some sports seem to threaten greater risks of harm than others. There’s a limit to how much harm a juiced-up cyclist or baseball player can do to other, non-juiced competitors. But sports where athletes pit themselves not against an inanimate ball or other object, but rather the large, heavy, and muscled bodies of other athletes, such as American football players and athletes in the so-called combat sports (such as martial arts) are more of a threat. It’s like facing the Incredible Hulk, which is is dangerous even if you’re The Thing.

In a commentary last year about a MMA fighter accused of doping, “PED Use in Combat Sports Should Be a Criminal Offense,” Forbes.com’s Brian Mazique argued that if true, his “fight was an assault, not an athletic competition…. [I]t stopped being a sport the moment the PEDs went into his system,”adding that “offenders should face a judge and jury.”

Of course, another reason PEDs are banned is that they are considered cheating. Those that do use them not only have greater strength and stamina than nonusers, but may be less vulnerable to injury and able to recover more quickly. But athletes who can afford better equipment and trainers or who are born with a genetic superiority also have an “unfair” advantage.

In Kurt Vonnegut’s story “Harrison Bergeron,” all such genetic advantages are eliminated through the mandated use of handicaps – not just weights for athletes but also distracting ear buzzers for the especially intelligent and clown noses for the handsome and pretty.

Maybe the real danger of PEDs is that they are unregulated, used in secret by trainers and physicians who are not always qualified.

Saturday Night Live once imagined an all-drug Olympics where PEDs were not only permitted, but encouraged, removing the cheating argument, but reinforcing the harm argument by showing a weightlifter so crazed that he ripped off his arms while attempting to lift a weight that was far too heavy. No rehab treatment facilities can fix that.

BIO: Stephen Bitsoli writes about addiction and related topics. A journalist for more than 20 years, and a lifelong avid reader, Stephen loves learning and sharing what he’s learned.